By Laura Bennett

Lately, I’ve been on a journey to be more compassionate towards myself. For me, this has meant learning to offer more compassion towards the thoughts, sensations, emotions, perceptions, and habitual patterns that arise. This journey has also naturally lent itself toward learning how to truly receive compassion. When I say compassion here, I mean self-compassion as the art of befriending reality as it is and tending to my own suffering with gentleness, care, and presence. This talk is borne out of my own journey with self-compassion.

I say journey because it’s really much harder than it seems. I keep finding that I need to recenter myself, recalibrate towards compassion for myself. Even in this practice of trying to offer myself more compassion, I have noticed that I can become almost…militant in a way that is not acting from compassion. It’s like in making self-compassion the goal, it becomes a concept to live up to, a way to measure myself. Ultimately, I’ve realized, if I am not careful, I actually end up using compassion as a way to judge myself more. It’s like…oh wow, I can’t even do compassion right. It becomes another way to judge myself.

As some of you may know, I started a master’s degree last fall, with the goal of becoming a hospital chaplain. The program I am in is very contemplative by nature and requires me to engage in meditation and contemplative practices as part of the program and part of my own spiritual journey. So, I think I went into the program with an expectation of how it might affect my relationship with myself, my thought processes, my world. I was, in all honesty, expecting to feel lighter, to feel a greater sense of equanimity and harmony. Instead I found that as I deepened my mindfulness and meditation practice, distressing emotions were arising more frequently. I noticed that I started to get really agitated and frustrated on a daily basis for what felt like no reason. I thought there was something wrong with me, that I should be feeling more peaceful, more calm, more this or that, but instead I was feeling more frustration, more anger, more agitation. Or at least, I was noticing these emotions more readily.

I have since realized that this was all part of the process of becoming more aware of these feelings and my reactions to them. Rather than habitually suppressing these emotions or turning away from them or sweeping them under the rug (as I was used to doing), I was, through meditation, removing the rug of delusion, the rug of aversion that kept me from feeling these emotions. I wasn’t necessarily more angry or negative, but all of the dust had gotten kicked up and I could see it more clearly.

And then, to make matters worse, I began judging myself for this. This is where the real suffering began—not in the anger or frustration itself, but in my response to it.

Many of you who have been part of this fellowship for a while have probably heard the Buddha’s teaching of the second arrow. In this teaching, the Buddha tells us that when we experience pain—physical pain, emotional pain, loss, disappointment—it’s as if we’ve been struck by an arrow. That first arrow hurts, and that pain is unavoidable. It is part of being human. But then, so often, we pick up a second arrow and shoot ourselves with it. The second arrow is everything our mind adds: the stories, the judgments, the resistance, the self-criticism. Thoughts like: “Why am I like this? I shouldn’t feel this way. I should be better by now.”

Our fellowship member and fellow practice leader Steve aptly calls this “should-ing” on ourselves. That phrase, lately, has been helping me get out of this pattern, or at least helps me notice what I’m doing. To this end, I’ve begun noticing the word “should” in my thoughts more consistently; Rather than berating myself for using this word, I’ve started to see it as an invitation for me to notice how I might be putting unnecessary pressure or expectations on myself. I am learning to notice how certain tendencies and patterns of mine, like “should-ing” on myself for example, actually produce suffering for myself and cut me off from being intimate with life as it is.

As Thich Nhat Hanh said:

“The art of happiness is also the art of suffering well. When we learn to acknowledge, embrace, and understand our suffering, we suffer much less. Not only that, but we can also go further and transform our suffering into understanding, compassion, and joy for ourselves and others.”

I am learning, slowly and imperfectly, to allow more spaciousness around my experience. Instead of punishing myself or judging myself for not being this or that—I am learning to be more gentle. I am learning to be a kind, friendly, open-hearted witness to myself and to what is, rather than immediately trying to fix, correct, or improve the moment. I am learning the subtle yet transformative art of self-compassion.

As Max Ehrmann writes in his poem Desiderata:

“Beyond a wholesome discipline, be gentle with yourself.

You are a child of the universe no less than the trees and the stars;

you have a right to be here.”

Or as Sylvia Boorstein so sweetly tells herself when she is struggling:

“Sweetheart, you are in pain. Relax. Take a breath. Let’s pay attention to what is happening. Then we’ll figure out what to do.”

This, to me, is the voice of compassion—true compassion, which is not urgent, it is not demanding, it is not corrective, but it is intimate and kind. It is gentle and tender.

Something else I’ve been noticing in relation to this practice is that even when I begin to offer compassion to myself, it can still be hard to receive compassion from others. It can feel natural to give care, understanding, and kindness to others, but when someone turns toward me with compassion, I feel a desire to deflect it, or to minimize it. I’ve noticed that when someone shares compassion with me, I have, for whatever reason, been conditioned to feel like I need to dismiss my own pain or come up with a positive way to reframe the situation to put us both at ease. In doing this though, I am not actually receiving the compassion that is being given. I am realizing that denying compassion is also a way of keeping distance—from others and from reality as it is. In practicing self-compassion, I am seeing more intimately how unconditional and vulnerable true compassion really is.

The Dalai Lama puts it very plainly:

“If your compassion does not include yourself, it is incomplete.”

I used to see this as a judgement, a criticism that revealed a defect in my compassion. Now, I see that self-compassion is the foundation for true compassion towards all of life. In self-compassion, I can embrace the fact that my own experience of life is imperfect, and I can appreciate that we all, often, produce suffering for ourselves in our own unique, foolish ways. This allows me to meet myself and others exactly where we are, with a sense of compassion for the human predicament that we all are experiencing.

For me, including myself in my practice of compassion means befriending everything that arises in my field of experience with unconditional compassion; it also means practicing receiving compassion with a sense of openhearted acceptance. This acceptance requires being vulnerable, it requires being open to the raw depth of my experience without trying to fix or control any of it.

Honestly, this practice has been more challenging than I thought it would be, but like most things, it is another reminder that there are no fixed answers or certain solutions. Self-compassion isn’t a destination that I am going to arrive at; it is a practice that I will continue to cultivate throughout my life. It is also a practice that, oddly enough, is best practiced in the relational space of a sangha because sometimes, the way that compassion reaches us is through other people—through a listening ear, a shared silence, a gentle reminder that we are not alone. Allowing ourselves to receive that compassion is itself a profound act of practice.

In our fellowship, we often speak of “come as you are” as the heart of the path. This is not a casual invitation–it is a transformative practice of compassion, vulnerability, acceptance, and honesty. It is the Middle Way brought into everyday life.

“Come as you are” allows me to show up without having it all figured out. Without being perfect. It even allows me to let go of the need to be good. Coming as I am means I can loosen my grip on the desire to be liked, the compulsion to perform, the quiet fear of not being enough. It allows me a place to practice true compassion.

As our practice manual says, it allows me to “let go of the stories and delusions that have hindered my freedom for so long.”

Here, I can show up and offer my studentship. I can learn from, with, and among my kalyāṇa mitras—my spiritual friends, my fellow travelers—as we reflect and embody the Dharma in our own imperfect, beautiful ways. I can be a humble student of the Way.

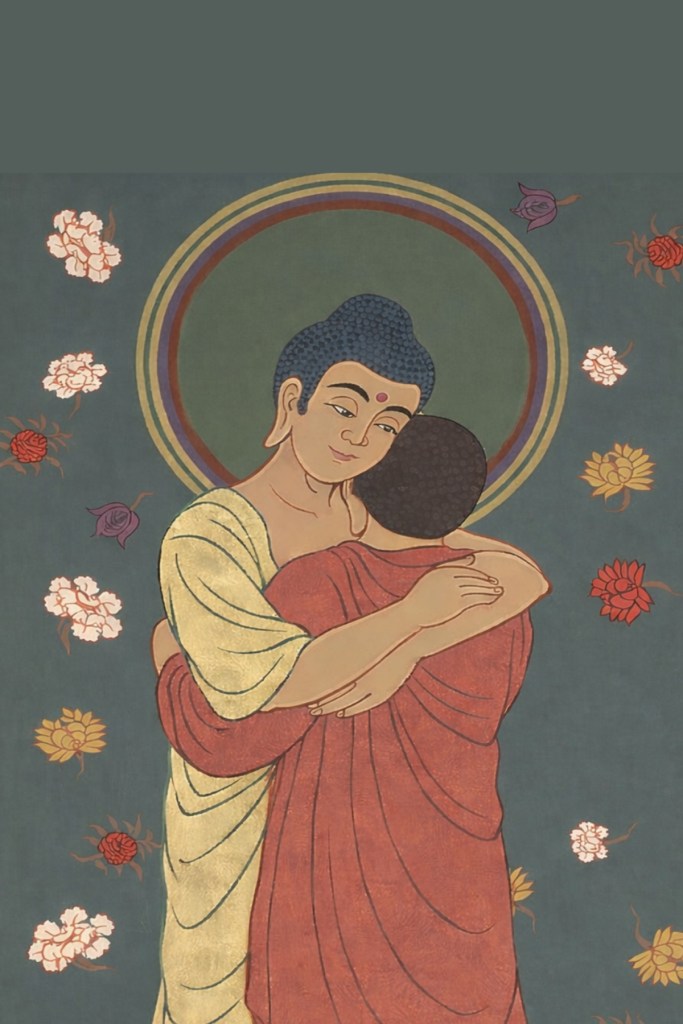

I can relax into the deep knowing that I am held by something larger than myself. I am held by the refuge I take in the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. I am held by boundless compassion—not because I have earned it necessarily, but because it is boundless and thus holds all of us.

Nobuo Haneda, in Dharma Breeze, writes that “According to the teaching of the Larger Sutra, the Innermost Aspiration meant “the aspiration to transcend the dualistic way of thinking (i.e., the thinking that compares good and evil, pure and impure, happiness and unhappiness).” It also meant “appreciating all things that one encounters in this life as indispensable conditions for the fulfillment of one’s life.””

According to Nobuo Haneda, when Shinran met his teacher Honen, “he heard the voice of the Innermost Aspiration speaking from him. It said, “Shinran, you don’t have to perfect yourself. Forget about your calculating mind, your dualistic mind! It is all right to be what you are. A perfect world already exists. Something perfect, the Dharma, already exists. You are already being embraced by it. The entirety of your being, including all your flaws and imperfections, is part of the Dharma reality, the wonderful reality. Nothing in your life is meaningless or wasteful. Even what you consider evil and impure has meaning. It is an indispensable component of your life. Just awaken to the fact that you are already being embraced by the Dharma reality!””

The Dharma invites us to embrace ourselves just as we are. We do not need to strive to be perfect or flawless—we don’t need to punish ourselves or correct our foolishness, but to awaken through it.

This is what I’m learning in my lifelong practice of compassion. I am learning that being compassionate toward myself isn’t about becoming perfect; it isn’t even about becoming better necessarily—it’s about becoming real. It’s about becoming a humble student of the Way.

Everything that arises in my life and in my emotional landscape is part of my journey of studentship. The important part, for me, has been learning to soften and be gentle towards whatever arises, with curiosity rather than judgment.

I am learning to relate to emotions not as problems to solve, but as signals—as messengers asking for attention. When I find myself frustrated with myself or with another, this is not a failure of practice. It is the very moment when I am invited to soften my resistance and open my heart.

The sticky, repetitive places my thoughts return to are not defects. They are messengers.

Compassion means to feel with. Compassion asks for intimacy with life, with people, with situations as they are. The opposite of intimacy is distance.

In compassion, I am asking—Can I be intimate with this moment as it is? Can I be intimate with this emotion as it is? Can I be intimate with this person as they are?

I hold these questions with patience, without demanding answers. I listen to what arises. Compassion asks me to be a gentle witness, to feel with, to be openly curious as each moment arises, evolves, and dissolves in endless awakening.

When I allow myself to stay with an emotion—the rawness of an emotion—I notice that it has an arc. It arises. It peaks. It passes away. Like everything else, it is impermanent. In seeing this, spaciousness naturally appears.

As Christina Feldman says in her book entitle Compassion:

“Compassion is concerned not only with how you receive others but how you receive your own mind and heart. At times you are afraid, agitated, or cruel. These are moments of suffering. Anger, fear, and judgment are not in themselves obstacles to compassion, but they become obstacles when they are left unquestioned. In themselves, they are invitations to compassion.

Compassion includes the willingness to embrace in a loving and accepting way all those moments of resistance and judgement.”

A few years ago, I wrote a poem that feels like it belongs here. I didn’t know then that I was touching on this very practice that has become so integral to my daily experience.

the flower of you—

cultivate compassion

for yourself, for those around you, for the world

like you would cultivate a seed—

tend to it, understand it, care for it

pour the water of understanding

on the seeds in your heart

until you are rooted in compassion

until you are a sunflower

pointed towards the sun of love, compassion, understanding

when weeds of suffering grow,

remember that you are the garden and the gardener;

when you are mindful of the suffering,

you may let it consume you,

but just as you can be mindful of suffering,

you can be mindful of the joys and wonders of every moment:

the flowers around you,

the flowers within you,

and the flower of you.

The training ground of compassion does not begin with heroic acts or perfect understanding. It begins with the small irritations, the everyday moments where we usually turn away from ourselves.

So now, when I ask where compassion is needed in my life, I ask something very simple:

Where am I distancing myself from reality as it is?

Where am I closing my heart to my own experience?

And each time I notice that distance, I hear again the quiet invitation of the Dharma, the vow of boundless compassion, saying: Come as you are. You are already held.

Now, I’d like to hear from all of you–what is arising for you in relation to this talk?

Where in your life or in your habitual patterns or thought processes could you offer more compassion to yourself? Where can you soften to what is?