DHARMA TALK by CHRISTOPHER KAKUYO

Today, I want to share a few thoughts on humility. Some years ago, I came across a profound teaching by Nubuo Haneda in his book Dharma Breeze. In the first chapter, he recounts the origins of the Shin Buddhist tradition when Shinran meets his teacher, Honen. Here is the passage.

“When Shinran met Honen, Shinran realized that he had had a shallow view of Buddhahood – his thoughts on the subject went through a total transformation.

Before Shinran met Honen, Shinran thought that the Buddha was a good and wise person, a holy person who possessed wonderful virtues. To become such a Buddha, Shinran attempted to purify himself by eliminating evil passions. But he could not attain Buddhahood. Not only was he unable to become a Buddha, he was feeling more and more depressed and miserable. He could not understand what was wrong. His goal of Buddhahood had seemed far away. When Shinran met Honen, Shinran saw a Buddha in him. But the Buddhahood he saw in Honen was totally different from what he anticipated.

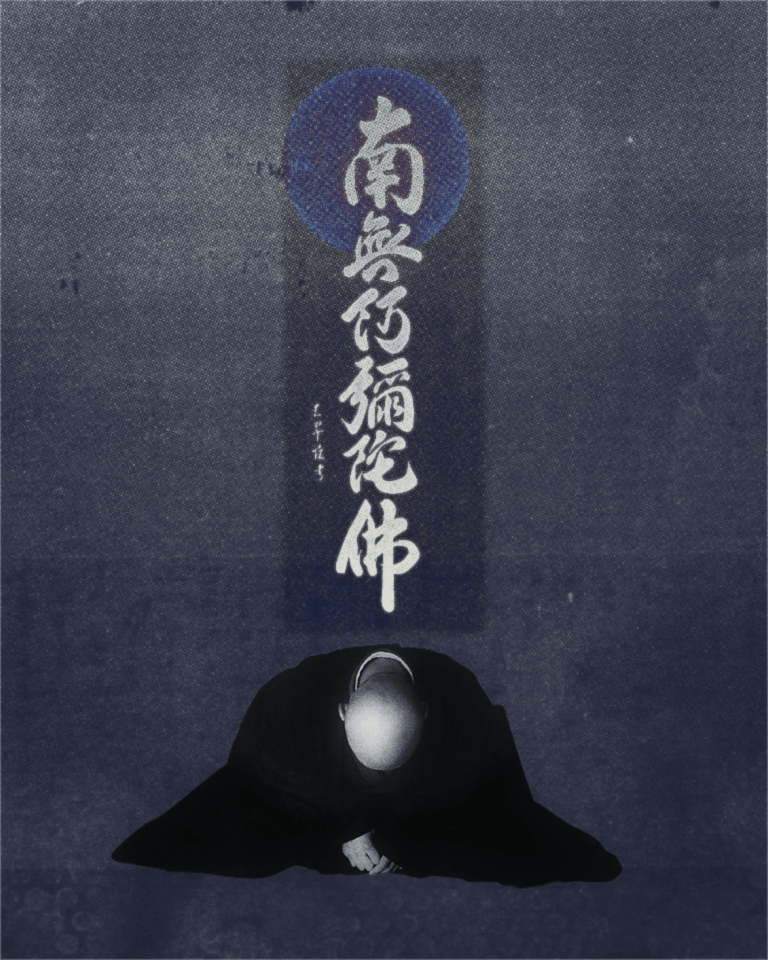

More than anything, Shinran was moved by Honen’s humility as a student. Honen identified himself only as a student Shinran said that learning from his teacher was the only important thing for him. Thus embodied the spirit of a Buddha by the name of Namu Amida Butsu or Amida Buddha. Namu, or bowing, is a part of the Amida Buddha’s name. The Buddha’s name symbolizes the humblest human spirit.

Before Shinran met Honen, he had thought that the Buddha was a teacher, a respected and worshipped person. But now, having met Honen, he realized that the Buddha was actually a student, a respecting and worshiping person.”

I love this teaching, and it has turned everything on its head.

The power dynamics are so different from traditional religious expressions. Here, the example of the highest ideal is not exalted by being brought down to earth – the Buddha is not a god but a student, a humble and respectful person. We are not below the Buddha, whose companions are on the journey to awakening. It is not surprising for someone who woke up sitting under a tree that reaches its roots deep in the darkness and is reaching for the stars.

How many of us have looked at religion or spirituality from that lens? Its purpose was about being good and becoming some holy person. Many of us, raised in the Christian tradition, are told to be perfect, as found in Matthew 5:38 :

“Therefore you are to be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect.

We will come back to this.

I remember years ago when I was LDS, and I was having a difficult time; I picked up a book titled The Unconditional Love of Christ and thought, this is what I need right now. I opened the book to the first page, which started with this quote – God Loves the Obedient. –

This was the opposite of “come as you are” of unconditional acceptance. The message I learned that day in that LDS bookstore was that God was perfect, and I was not – and would never be because the kind of obedience I was being asked to achieve was beyond comprehension. At the heart of my LDS experience was that God’s love was conditional, as was my acceptance into the broader community. God might as well have asked me to become a duck—because both were equally impossible. How can we relate to something that is the total opposite of ourselves?

Humans are uncomfortable with perfection because it is foreign to our experience. But that does not keep us from trying to be perfect – maybe because we have created this internal story that we will be loved, safe, and in control if we can become perfect or close to it. Maybe our attempts at perfection have more to do with our insecurity, fear, and failing to control an uncontrollable universe.

The biggest obstacle that prevents us from awakening is our “knowing.” I appreciate the lesson I received from Nobuo Haneda, which emphasizes that the most essential virtue on the Buddhist path is not perfection or holiness, but humility. We are referring to the humility of unknowing—the humility that allows us to be teachable, the humility of a student who begins their journey with the acknowledgment of “I don’t know.”

Humility involves all of us stepping onto the Buddha path, where we let go of the stories we believe to be true, examining them and their impact on our lives.

Another important aspect to consider is that our relationship with the Buddha differs from that with a God. A Buddha is not a deity but a being who is fully awake, fully aware of their ongoing role as a student. Haneda teaches us that the Buddha’s studentship is exemplified by his respect for and reverence towards nature. The Buddha embodies a form of studentship that we all can aspire to achieve.

Now, before anyone gets triggered by words, be a little patient. We can all speak the same language but carry different baggage. A respectful person regards others, considers others, and notices with special attention. Now, for our more secular-minded brothers and sisters – the word “worshiping persons” could be triggering. What does he mean by that, since Buddhas are not gods?

It simply means a sense of reverence – which means to “treat with respect, to esteem, to value – we value the teacher and the teaching, we appreciate all that supports us – we can see our gratitude practice in this same light. Reverence is at the heart of our awareness practice and the fruit of such a practice. I love this from Larry Dossey

.

“There is a way to partake of the universe — whether the partaking is of food and water, the love of another, or indeed, a pill. That way is characterized by reverence — a reverence born of a felt sense of participation in the universe, of a kinship with all others and with matter.”

And this is from C. Alexander and Annellen Simpkins in their book Simple Zen

.

“When we experience ourselves as one small part of nature, we feel reverence. Zen teaches that we should feel reverence for all beings, no matter how insignificant they might seem. From the enlightened vantage point, we should appreciate everything equally, from the most basic and small to the most complex and vast. Each has the whole reflected within.”

To be a Buddha, then, is to be a humble student, aware of our ignorance and a considerate person aware of others, with a sense of respect, deep gratitude, and awe for this human life we have been given. To be a Buddhist is to be humble and appreciative and embrace our perpetual studentship.

I love this quote from Raymond Lam: “Being humble is itself a spiritual practice.” This is not easy for us in the West. Too many of us equate humility with weakness and lack of self-confidence—this is a misperception of humility.

I have been reflecting on the roles of humility and gratitude, and I believe humility is a prerequisite for true gratitude. Often, we find it difficult to express gratitude because we struggle with humility. In my exploration of this topic and through conversations with others, I’ve discovered that many people have difficulty with humility because they have not truly experienced it; instead, they may have encountered its unhealthy counterpart—shame.

When we embody humility, we become open and willing to learn, displaying both sides of the leaf. In contrast, shame causes us to shut ourselves off from the outside world, leading us to bury our leaf in the darkest hole.

In this state of mind, when we encounter someone radiating compassion or remarkable skills, we often fail to see them as sources of inspiration. Instead, they serve as mirrors reflecting our insecurities, deepening our feelings of shame about our perceived failures. What could be a beacon of hope becomes a stark reminder of our shortcomings, suffocating any sense of gratitude.

On the other hand, embracing humility opens up a world of awe and acceptance of our limitations. It enables us to move forward without the heavy burdens of judgment and shame. With humility, we can let go of the relentless pursuit of perfection and our unrealistic expectations for others, allowing us to find peace in the imperfections that define our human experience.

The humble student learns from the adversities she encounters, rather than using them as justifications or rationalizations for harmful behavior towards herself or others, or retreating into a fortress of apathy. As we cultivate greater humility, we can release our failings instead of allowing them to fuel self-hatred or shame.

We can acknowledge our faults without feeling ashamed. Matthieu Ricard reminds us that Tibetan sages have long taught that the best teachings reveal our hidden faults. I appreciate these insights from Raymond Lam as well.

“Acknowledging my fallibility actually benefits me more than anyone else because I become mindful of my own limitations and allow others to help me. Most importantly, humility lets us open ourselves to receiving (and Taking Refuge in) the help of the Triple Gem: Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.”

As we all practice humility together, no one can claim to be superior. We are just trying our best, striving to follow the Perfect One and touch the imperishable essence of Buddha Nature within all beings. This openness connects us. Practicing in the community can help us on the path to healing and awakening by becoming more open and allowing others to help. Allowing someone to help is a manifestation of humility. It is at the heart of Namu Amida Butsu – “Come as you are.”

And here is one of the most important things about being a humble student at the heart of being a humble student and acknowledging that we don’t know. The “I don’t know mind” of Korean Zen Buddhism is at the heart of humility, which we have talked a lot about in our fellowship. The most honest and humble thing any one of us can say is, “I don’t know.”

And it can be one of the hardest. We live in a society that prioritizes knowing, even if that knowledge has no basis in fact. Conspiracy theories are a perfect example of the “cult of knowing,” but as Dizang, the great Chinese Zen master, has taught, “Not knowing is most intimate.” And Thanissaro Bhikkhu teaches is that humility is the willingness to learn. “That’s what’s meant by an attitude of humility: a willingness to learn from the little things, no matter where they show themselves.”

Shinran learned from Honen that becoming a Buddha was less about striving for perfection and, therefore, a destination and more in the ability to cultivate humility, gratitude, and awe.- and that we cultivate this through our perpetual studentship of the way. It is always by the journey and not the destination.

From an everyday Buddhist perspective and embarking on the personal path of studentship, we can learn to embrace the questions without the compulsive need for answers. In this kind of studentship, the questions are what we live. Because, as Rev Gyomay taught, life is not a problem to be solved.

I have found in my life that many times, the answers are less important than the questions. I want to share with you one of my favorite passages that come from Rilke in his book Letters to a Young Poet, where he writes –

“I want to beg you, as much as I can, dear sir, to be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves like locked rooms and like books written in a very foreign tongue.

Do not now seek the answers that cannot be given to you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.”

To me, Rilke speaks directly to the kind of humility that a Buddha represents—a student, a respecting and worshiping person.

What is a Buddhist? There are as many definitions as there are people. Today, our answer to this question is straightforward: a humble student of the way.

Now, that is something that I can be!

Christopher Kakuyo, Salt Lake City 2022