Today, I want to discuss rituals in relation to Buddhism and Buddhist practice, Before we begin, I want to share a few words and have you shout out the first thing that comes to your mind.

Faith

Belief

Prayer

Ritual

Evil

Sin

Most of us have left the traditions of our fathers and mothers and left it “back there.”

From my experience leading the Salt Lake Buddhist Fellowship, many who have left their previous religious tradition carry around a shadow and suffer from a reactivity to any religion—a post-religious reactivity PRR. It is easy to spot. When anything smacks of “RELIGION” with a capital R, it is a feeling of “get me the hell out of here.”

It can be a visceral reactivity to anything that seems or has a hint of religion. I think that is why Buddhism is attractive. There is no GOD per se; it’s just meditation and being compassionate – and it’s “scientific,” whereas religion is superstition and based on blind faith. Buddhism is the science of the mind; it’s basically just psychology.

Most of us have found the dharma through books and podcasts written from or about a Western mindset.

For many people, when they first attend a Buddhist gathering, they might be surprised to find it is not what they expected—all the prayers, bowing, and rituals.

The first point I want to make is that there is no Buddhism – Buddhism is not monolithic- there is a multiplicity of Buddhisms worldwide. In the Western world, we like our binaries, and In contemporary Western Buddhism there is a subtle segregation between more secular and more traditional forms and there is a subtle and sometimes not-so-subtle devaluation of more traditional Buddhist practices. I have heard plenty of Western Buddhists say that traditional forms of Buddhism are not “real” Buddhism.

In her amazing book Be the Refuge – Raising the Voice of Asian Buddhists. Chenxing Han talks very explicitly about the Western bias against more traditional expressions of Buddhism She talks about how there are two generally accepted assumptions that there are two different kinds of Buddhists in America, “Western” or “white” Buddhists—that— focus on meditation practice. These Buddhists tend to be more of rational and modernist-minded. Then there are “Asian” and “Asian American Buddhists ‘—who tend to prefer the more traditional and devotional rituals of chanting and bowing. She goes on to write,

“It is discomfortingly easy to guess which group is more likely to be denigrated as “superstitious” and which is more likely to be celebrated as “scientific.” Rational Buddhism vs Non-Sense Buddhism.

This is unfortunate and somewhat arrogant.

The practices of bowing, chanting, lighting incense, and reciting vows and prayers are not empty traditions from a less enlightened time, nor are they superstitious; quite the opposite.

And . . . do you feel like we are living in enlightened times?

Again I want to emphasize that Westernized Buddhism is not a more enlightened Buddhism – because we don’t worry about all the traditional Buddhist, non-sense. As one BD LM CJ Daiyo Sensei once said, “traditional buddhism has 2500 years of field testing, so you may not want to throw out the baby with the bath water.”

Ritual practice in Buddhism actually is an opportunity to approach the practice from a different angle. Ritual can become a very important door to practice. Bowing as practice and chanting as practice are two examples.

I appreciate this from Gil Fronsdal,

Often, Western Buddhists see rituals as superficial and distracting from the “real” work of practice. This view overlooks how rituals are practiced as much as meditation.

In the past and in the present, many Buddhists have used ritual practices as their primary way of inner transformation. For example, bowing is one of the most common Buddhist rituals. It can be powerful and evoke and strengthen a person’s reverence, gratitude, humility, and ability to let go of self-centeredness.

There is a great story in the Lotus Sutra of the Never Disparaging Bodhisattva, once one of my favorites – this bodhisattva’s sole practice was to bow to everyone he would meet and say

“I have profound reverence for you. I would never dare treat you with disparagement or arrogance because you will be a Buddha someday.” People did not like this. ” Who are you to say this to me?”

Many would mock him, others would beat him, but Never Disparaging was not discouraged. He would just back far enough away for the rocks not to hit and would continue – as he was dodging the stones and sticks

– I have profound reverence for you, I would never dare treat you with disparagement or arrogance because you will be a Buddha someday”.

In the practice of bowing is the embodiment of the utmost reverence for all human beings as future Buddhas.

Ritual is an embodied language, like dance, in which we communicate with movement and sound something from within.

It also challenges us to present not just our minds but our bodies. Our practice of the way is not simply focused on the one organ, the mind, but our whole being. I appreciate this from

John Dado Lorri Roshi,

In liturgy ( ritual) – expressing it in our gestures, voice, and thought, we renew, confirm, and restate our Buddha nature. We embody the life of a Buddha.

We have been talking about ritual, so this would be a good point to define it.

A ritual is defined by psychologists as “a predefined sequence of symbolic actions often characterized by formality and repetition that lacks direct instrumental purpose”.

I really appreciate that last part, where there is no instrumental purpose. The ritual itself—my bowing to you and us reciting words in a prescribed order—has no meaning on its own. These choreographed actions, both individually and collectively, provide us with meaning or teach us something in a more indirect way.

It is interesting that research done on ritual reveals that Ritualistic practices can help to bring a degree of predictability to an uncertain future. They convince our brains of constancy and predictability as “ritual buffers against uncertainty and anxiety“, according to scientists.

I want to share a little about my personal experience with ritual.

Since its beginning, our fellowship has had a liturgy or a set order of practice. Creating a safe place to practice a radical form of acceptance was necessary. I wanted our community to be more than a study group. In my mind, some liturgy would set apart what we were doing, transition us into a more deliberate space.

The set order of practice has changed a lot since we started. I recently started reworking it again. Ritual and liturgy need to be living things that give meaning (Symbolic) to the individual practitioner and the community.

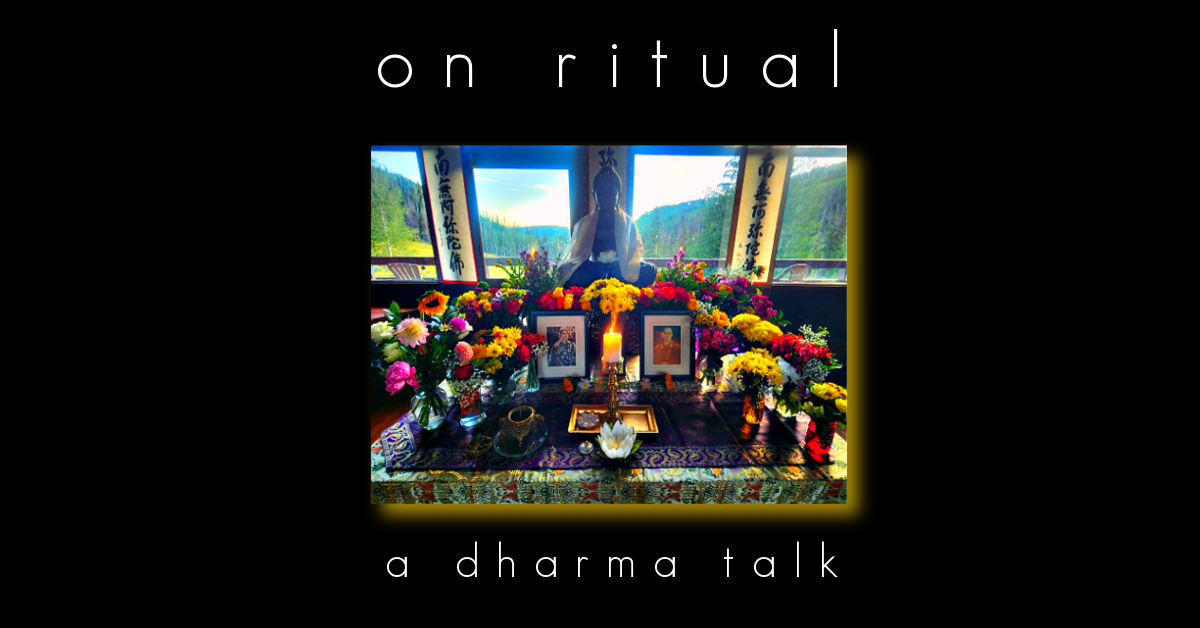

In our community, we bow often and recite vows. We have Buddha statues, Nembutsu scrolls, bells, candles, incense, and prayers. This is what our liturgy is like when we meet in person. We start by ringing a bell outside to let anyone who wants to attend, know that we are about to start and that they can join us. The bell ringer then walks inside and down the center aisle with the candle lighter, the bell ringer bows to the Buddha, then turns and bows to the candle lighter and then to their cushion. The Candle lighter then bows to the Buddha lights the candle and bows again.

Quick question: Why do we bow to the Buddha statue? Buddha is not a God, so why bow?

Great. Now the candle lighter, bows to the sensei, the community Right Center, and then Left.

Why do you think they do that?

The candle lighter then sits, and the practice leader rings the large temple bell three times, waiting until the sound completely fades before the next ring. Then, the leader leads the community into a guided meditation.

The stage is set. This is a very important point to make. One of the most ancient purposes of ritual is to help the mind focus on the important.

The purpose of ritual gatherings is to establish a space different from our daily routines. These gatherings facilitate a transition from the ordinary to the intentional, allowing us to engage more meaningfully. They create an environment where we can connect with the community, sharing common aspirations and values.

The prayers of the practice manual are recited out loud—our collective voices rise as one, not just a lone practitioner but a practitioner among practitioners. We connect in our mutual values and aspirations of wisdom, kindness, compassion, healing, and love.

Each step of our ritual is to guide the person entering our sangha space from the chaotic world of samsara and slowly enfold them into a more focused, safer, and intimate space. It is in such spaces that we are more likely to take mental and emotional risks—in such spaces, we learn to open ourselves up to ourselves, to others, and to the world.

Looking at how it is arranged, the first bell announces we are about to begin. The bell is rung quickly in repetition to represent the chaotic world and then slows down. The bell ringing and walking slowly toward the altar represents the slowing down of time to start bringing us to the present. As we follow the fading ring, the three long bells slow our minds and breathe down even more.

Our guided meditation, with its line of “breathing in breathing out I am aware that I am breathing in and out,” brings our focus to our embodiment. We go from breathing to scanning our body for tension, more embodiment, back to the mind, with the words,

“Help us practice the art of letting go, letting go of the need to know and the need to control, and help us realize there is nowhere to go and nothing to do.”

If we let them, each of these steps and rituals helps us to become more present physically, mentally, and emotionally. I want to say that one more time: If we let them, these steps, these rituals help us to become more present physically, mentally, and emotionally.

By themselves, scrolls, Buddha statues, candles, and whatever else you incorporate are nothing but ornamentation. Material objects and ritualistic actions have no meaning until we allow ourselves to infuse meaning into them. It’s as true about your favorite stuffed animal, your grandfather’s watch, or your lucky penny. We give these things meaning. And giving them meaning contributes to our lives having meaning.

It can be difficult for us Westerners who leave a Judeo Christian tradition, to get past our resistance to ritual as something superstitious or empty. It can cut us off from another meaningful aspect of practice.

Anne C Klein writes that

“A vital key to ritual power is to remain present to our embodied experience. Neither mind nor body can navigate this journey alone.”

That is one of the things I appreciate about ritual is that it can help me get out of my head.

Before our gatherings, each participant receives a practice manual with prayers and affirmations. These prayers and affirmations contain the teachings of the Buddha. Still, more importantly, they allow our community to express individual and collective commitments to healing a wounded world and following in the footsteps of the Buddha.

We also incorporate chanting—especially in the traditional Taking Refuge. We do that to acknowledge and connect to the 2500 years of our tradition and to all those who have preceded us. We also use candles and incense lighting to pay homage to the Pure Land tradition that informs so much of our teachings.

The vows and prayers help to cultivate a space where the individual can connect the collective— the community – with our shared aspirations and values.

Many of these rituals have been done in person, and some can be done online.

Here is an important point: Our community is diverse in that it consists of all kinds of practitioners, from avowed atheists to those who believe in a divine force. Some approach Buddhism as a philosophy and others as a religion. What a person believes is really not our business. What unites us is our commitment to following the way of the Buddha.

Over the years, I’ve had lots of conversations on why all this bowing, or these affirmations, why this ritual, you should change it, and more people will come. I would smile and say it’s just what we do. If you don’t like bowing, don’t. If you don’t like reciting the vows or chanting, don’t. You are still welcome. Doing these things won’t make a good Buddhist or a bad Buddhist. It is just what we do here in our community.

There have been different responses over the years to our ritual practice. Years ago, we had a small chapter of the fellowship in Utah County, and a few of the members there pushed to eliminate our liturgy. They wanted to get rid of almost all of it. They kept on saying that it wasn’t necessary, that it wasn’t real Buddhism. Our practice leader stood firm. Our practice form is part of our practice as a fellowship; it is part of the personality and temperament of our community.

Another response was how someone in our community dealt with all the bowing. One member told me that he really resisted bowing; he didn’t like it, and I told him to not do it then. If it doesn’t work for you, don’t do it. A few years later, when he sought refuge on the morning of his Ti Sarana, I watched him leave his tent, face the rising sun, and bow to it. Despite his initial resistance, bowing gradually became a part of his practice of being present in the world.

Ritual is simply a door to another language of practice, language of intention, mindfulness and body awareness. It serves many functions for the individual and community.

What I would like to do now is to go to our practice manual.

I want us together to let ritual do what ritual does. I want to practice what we just shared. As we read the prayers and affirmations, as we vow to be there for one another – let your attention and intention fill your voice as your read them outloud. Raise your voice a little more than usual. As you chant, sing a little louder than usual. As you recite the line, really be present with what you are saying – let this aspect of practice work on you.

CONCLUSION

I would love to challenge all of you to look for ways to incorporate some kind of simple ritual into your practice. Incorporating heart, mind and body. The great thing is you have all the freedom in the world to make it your own – to make it meaningful to you.

I love bowing. Bowing to my cat in the morning, bowing to my bed when I wake up – bowing to the sun as it rises, bowing to the flower on my altar. – maybe there is something that connects you to stillness – lighting a candle, or incense, maybe chanting a mantra – experiment, play with ritual. It does not have to be all serious –

I would like to end with a quote, From a Einstein

“Play is the highest form of research.”

I challenge you to play in the field of ritual and see what happens.